It is not easy to represent the unrecognised Republic of Artsakh, but the stakes could not be higher: extinction.

In Artsakh, the distance between a minister and a citizen is so small. Artsakh FM

STEPANAKERT, MARCH 2, ARTSAKHPRESS: It is not easy to represent the unrecognised Republic of Artsakh, but the stakes could not be higher: extinction.

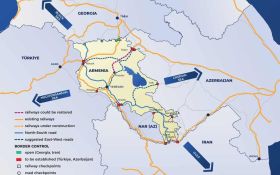

When Karen Mirzoyan, its “foreign minister”, wants to hold an international meeting he has to drive six hours from Stepanakert, Artsakh’s capital, to Yerevan, along the mountain road that forms its only link to the outside world.

Sometimes the 3,000-metre high passes are blocked by snow.

In other places, the minister drives behind earth dykes to shield his car from potential Azerbaijani fire.

Artsakh, which is home to some 150,000 Armenian people, has an airport, but its warring neighbour has threatened to shoot down any plane that used it.

Meanwhile, foreign envoys do not call on Mirzoyan at home because European, Russian, and US diplomats are forbidden from going to Stepanakert to maintain neutrality.

When he gets to Yerevan, or flies onward to the EU, the minister holds meetings in private conference rooms instead of official buildings.

He also keeps quiet about them in order not to embarrass his interlocutors.

He told EUobserver in an interview that he had met with “EU officials” and other “high-level [EU] people, but not at the level of foreign ministers of big powers”.

The jovial 52-year old was born in Artsakh, which used to call itself the Republic of Nagorno-Karabakh. He left for Armenia and joined the Armenian foreign ministry, before stepping down to take the Artsakh post.

“It mightn’t be very good for your [professional] ambitions, but being the foreign minister of a non-recognised country is more enjoyable,” Mirzoyan said.

“I’m not bound by norms of diplomatic protocol. I’m more free,” he said.

He said Artsakh’s story inspired him.

“The fact I represent a small nation on the outskirts of Europe that was able to survive against all the odds, was able to win the war and build a democratic state, gives me strength and creativity,” he said.

He said proximity to people also inspired him.

“In Artsakh, the distance between a minister and a citizen is so small. You’re foreign minister for a few hours a day, but when your work ends and you walk in the street, you’re an ordinary citizen,” he said.

By Andrew Rettman